Old Friends, New Beginnings: Hutong Development and the Businesses Rising Again From Beijing’s Brick Dust

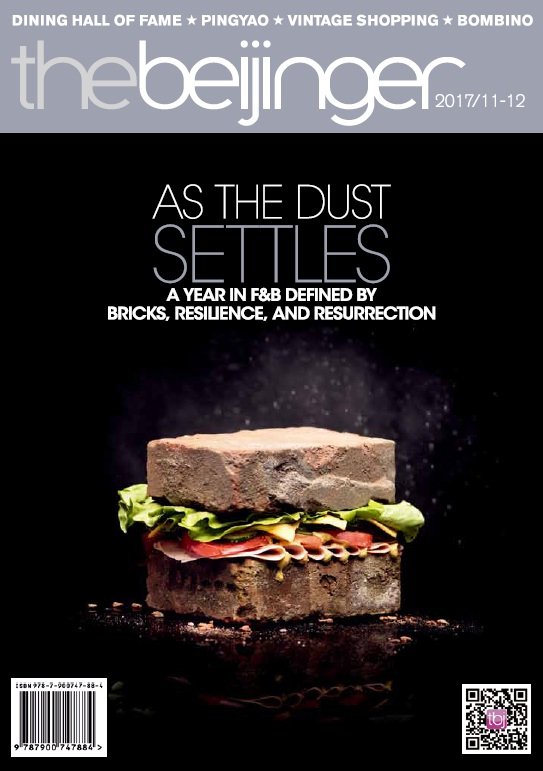

The shakeup to Beijing’s food and beverage industry in 2017 was unprecedented, even to those most seasoned and hardened to the fluid nature of the scene. For those of us who watched on, it was difficult to keep up with the closures, fatality after fatality squeezing owners and taking away their projects of love as authorities swept through the city with a vow to “beautify” and reclaim. For those directly affected by the tumult, answers were elusive but the results couldn’t be clearer – windows disappeared, business dried up, and licenses were ultimately revoked. However, we can see this episode as more of a reshaping of the landscape rather than a complete decimation. Many of the businesses that fell have since cut their losses and gone elsewhere to begin again, this time working outside of the loopholes and gray areas that Beijing building planning, or lack thereof, had allowed over the past 20 years of growth.

Since 2008, there has been a conscious decision by the government to polish over some of the more unsightly aesthetic details – chai-ing of some unlicensed properties, the painting of walls and doors, repaving of the streets etc. – but this newest iteration of the campaign has taken a much deeper line of attack, prioritizing spatial organization through the removing doors and reassignment of courtyard entrances, and making it difficult to predict what comes next.

Rosie Levine of the grassroots NGO Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center (CHP) explains that the development that is occurring in the hutongs stems in some part from the “long-set ideology that hutongs are bad, they’re slums, they’re overcrowded and overpopulated and the future is more in high-rise buildings. Anything that is of cultural value in the hutongs is the aberration, rather than the norm, and that attitude is still quite prevalent in some aspects of city planning in Beijing … It’s a very narrow vision of what the city can look like rather than allowing for the diversity that had blossomed.”

Levine subscribes to the official line that the project is in effect an attempt to reduce and cap the city’s population at 23 million, saying, “That would mean removing those migrant workers and laborers who come in and often set up more informal businesses. There’s a general idea of modernization when it comes to the city which doesn’t involve a lot of the things that have been features of the city up until now: smaller local markets and community-based xiaomaibu, preferring to have all the commerce happen on main streets rather than in the hutongs themselves.” F&B businesses were therefore just one victim swept up by the bricking.

Despite being fully licensed, Paca Lee of Fangjia Hutong favorite Ramo, was one of those forced out, since reopening in a designated business building in Jintai Xilu, Lido. Lee laments having to leave the hutongs, but what she was most disturbed by was some of the reactions from people in the neighborhood. Tearing up, Lee describes how, “I saw comments about the bricking [online] that said this was the best thing that had ever happened. I saw the worst side of people - lots of people that I don’t even know, not even my neighbors, came and were laughing outside – people who had nothing to do with it.” Lee adds, “The older generation perhaps see the hutong as somewhere that should be quiet and they prefer it the old way. I think most people are happy with the changes but Beijing is a modern city – what was best 50 years ago may not be the same now – it has to change.”

READ: Those That Benefited From, and Were Slighted By, the Chai-ing of 2017

Zak Elsmari, a Beijing resident for 11 years and owner of the deceased Fangjia Hutong rendition of his Fang Bar, but who has since moved to Jiaodaokou’s Shoubi Hutong, takes a less sentimental stance. He says he has noticed a shift in the kind of people that were hanging out in Beijing’s alleyways and the proliferation of what he calls “popcorn hutong-goers,” those who frequent trendy watering holes because “it had become a thing.” That’s compared to past patronage; “people who knew their history and knew their language,” a change from “when I would find a small bar that only people in the hutongs knew about or had made the effort to go to.” The authorities are well aware of that tourist potential, gradually tapping into it with large site-specific renovation projects like Qianmen’s Pedestrian Street, Wudaoying, and of course, the infamous, albeit for different reasons, duo of Nanluogu Xiang and Sanlitun's Dirty Bar Street. It’s safe to assume that once the small fish are out of the way, a standardization of commercial and residential centers will continue to emerge.

From these examples, it’s clear that this year was a marked departure in the way that businesses, F&B or otherwise, would be permitted to operate in Beijing, now foregoing hutong-based spaces for larger, more legitimate premises. The scheme’s opaque workings, coupled with permissions that operate outside of the law mean that the industry will continue to guess where lines lie and what steps will be taken next to elevate Beijing to the heights of an archetypal city. Thankfully, Beijingers are a hardy bunch, and as Elsmari surmises, “I’ve seen stages where things have gotten tough … but everyone seems to find a way.”

This article first appeared in the Nov/Dec 2017 issue of the Beijinger.

Read the issue via Issuu online here, or access it as a PDF here.

More stories by this author here.

Email: tomarnstein@thebeijinger.com

WeChat: tenglish_

Instagram: @tenglish__

Photos: Dave's Studio