Mandarin Monday: Ancient Word Games to Practice Your Idioms and Poems

Mandarin Monday is a weekly column where we help you improve your Chinese by detailing learning tips, fun and practical phrases, and trends.

When it comes to learning Mandarin, there's fluency... and then there's fluency! That is, it's one thing to be able to converse with folks in your day-to-day life, however, Chinese idioms and references to classical poetry, of which there are many, is something else entirely. Simply put, idioms and poetry are the gatekeepers blocking people from moving to the next level of Chinese proficiency. Nevertheless, being able to comprehend and utilize them at all the right times will not only be a gold star on your unofficial Chinese transcript but also come in handy when explaining complicated, abstract ideas, altogether resulting in a deeper, more robust appreciation for this historic language. To help you memorize a few idioms and poems in a fun, decidedly non-textbook way, we found two games dating back to the time of ancient scholars.

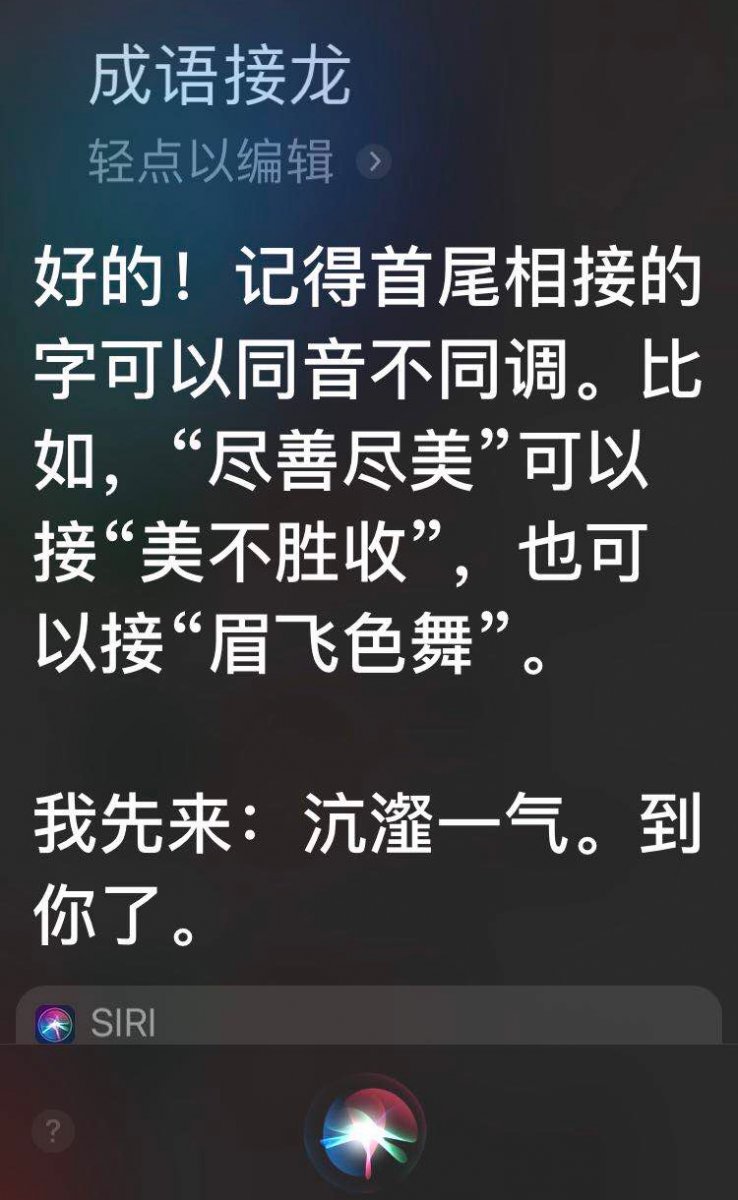

成语接龙 chéngyǔ jiēlóng Chinese idiom solitaire

A classic game that is popular among kids for idiom learning and memorization, the rules are pretty simple: Basically, just have someone name an idiom and then the next person needs to come up with another idiom that begins with the same character as the last one of the previous idiom. For beginners, people don’t have to use the exact same character to continue the game as long as the pinyin matches. Of course, you can also level up by setting new rules, such as all idioms can only be used once, the meaning of the idiom has to be positive, the idiom can’t include numerical homophones, etc.

You don’t need to prepare much for this game – a mobile phone or an idiom dictionary (for challenging a word or phrase) is enough. You can either play with friends, solo or even with Siri on your phone.

Here is an example of gameplay, with bold characters connecting the two idioms.

A: 哭天抢地 kū tiān qiāng dì

Praying for God's mercy in screams and bumping one's head to the ground. (An idiom that describes someone's extreme reaction after hearing horrible news.)

B: 地动山摇 dì dòng shān yáo

Shake the mountains and the ground. (Can be used to literally describe an earthquake or something large in size and high in volume, or the impact brought by an intense conflict.)

C: 摇旗呐喊 yáoqínàhǎn

Waving the flag and cheering. (Can be interpreted as "Bang the drum for somebody.")

D: 喊冤叫屈 hǎnyuān jiàoqū

Cry out about someone's greivances

E: 屈打成招 qūdǎchéngzhāo

Confess to false charges under torture

F: 招蜂引蝶 zhāo fēng yǐn dié

Allure the bees and butterflies. (A negative idiom to describe people who attract other's attention, especially from potential romantic partners.)

飞花令 fēihuā lìng Poetry drinking game

Sorry college kids, but you did not invent drinking games. In fact, they've been played in China for at least 2,000 years, not only serving as an ice breaker for guests during a banquet but also as an impressive way for ancient intellectuals to show off their talents. Among all of the classic Chinese drinking games, 飞花令 fēihuā lìng (lit. The order of flying flower) is arguably the most challenging. This game requires all participants to recite a sentence of a poem that contains the character “花 huā flower,” and the place of this letter in the sentence needs to match with the order of the participant. For example, for people who start the game, the character ”花 huā “ needs to be the first character of the verse, while the next person needs to come up with a sentence that has ”花 huā “ as the second letter, and so on. All participants need to use the same form of the poem – usually a five- or seven-character quatrain for Tang poems – however, you can improvise your own verse if you can’t think of any fitting sentences.

The game also got its name from a famous verse “春城无处不飞花 chūnchéng wú chù bù fēihuā Nowhere in the capital doesn’t have petals floating in the air” that depicts the scenery of Chang’an during Qingming – or Tomb Sweeping Day. The reason the character “花 huā” is required is likely down to the frequency with which it is used to depict objects and the fact that it is a common symbol in Chinese poetry, thus suiting the vibe of the feast since it is a tradition for scholars to hike into nature and have a picnic in spring. But in the modern version, you can switch it with other commonly used characters, such as “月 yuè moon,” “云 yún cloud,” “夜 yè night,” or “春 chūn spring.”

Here is an example of the gameplay, with the bolded character marking the right place for “花 huā” to appear in the poem.

A: 花近高楼伤客心 huā jìn gāolóu shāng kè xīn

The blossoming flowers close to the tower broke my heart, as a wanderer who was forced to leave my hometown and previous homes.

B: 落花时节又逢君 luòhuā shíjié yòu féng jūn

Didn't expect we would meet again in this flower falling season

C: 春江花朝秋月夜 chūnjiāng huā zhāo qiūyuè yè

The flowery mornings in the spring and the moonlit nights in autumn

D: 人面桃花相映红 rén miàn táohuā xiāngyìng hóng

Your beautiful face and the peach blossom share the same lovely redness

E: 不知近水花先发 bùzhī jìn shuǐhuā xiān fā

People don't know that plum blossoms by the water bloom early

F: 出门俱是看花人 chūmén jù shì kàn huā rén

Wherever you go, there will be crowds of flower viewers

G: 霜叶红于二月花 shuāng yè hóng yú èr yuè huā

The red leaves in autumn have a more vibrant red color than the flower in spring

Read: Mandarin Monday: Good Morning Salarymen and Salarywomen

Images: Zhihu, Apple, Zeus Zou