Holiday Walk: Take a Stroll Through History Around Beijing's Lakes District

Weekend Walk is your guide to getting away in the city using nothing but your own two feet.

The Line 6 Beihai Bei (Beihai North) Metro Station Exit B is located just across the street from Beihai Park's north entrance, making it a convenient place to start this weekend's walk around the lakes often referred to as “Houhai.”

Actually, 后海 Hòuhǎi – or “Back Sea” – is the name of just one of the lakes in the chain known to Beijingers as 什刹海 Shíchàhǎi, the “Sea of Ten Temples,” a reference to the many religious sites, palaces, mansions, and other important courtyards which defined the area in the imperial period. During this walk, we’ll stroll along the banks of the lakes and past some of the landmarks which still survive.

Walk a short distance east along Dianmen Xidajie (Dianmen West Street) to #57 and the Beijing Shichahai Sports School. Founded in 1958, many of China’s most famous athletes, including table tennis hero Wang Tao and badminton aces Dong Jiong, Zhang Nan, and Liu Yuchen, trained here. Perhaps the most famous alumni internationally are action stars Jet Li and Donnie Yen, who studied Wushu at the school in the 1970s.

Continue north along Qianhai Xijie (Qianhai West Street), following the western edge of the Sports School campus. On the west side of the street, you'll find the entrance to the former home of Guo Moruo (1892-1978).

As a scholar, Guo had a wide variety of interests, including literature, archaeology, art, history, and poetry. Likewise, as chairman of the China Academy of Sciences from 1949 until his death, aka the Mao era, he served as the in-house intellectual. You have seen Guo Moruo’s handwriting even if you didn’t know it. His calligraphy graces many familiar buildings in Beijing and is even incorporated into Bank of China's official logo.

A short walk north past Guo Moruo’s house is a T-Junction. To the left is the entrance to Prince Gong’s Mansion. Prince Gong (1833-1898) was the more talented younger brother of a terrible emperor. Part of the 1861 coup, which eventually brought Empress Dowager Cixi to power, Prince Gong became the public face of the Qing Empire and a liaison with the foreign powers stationed in Beijing. Prince Gong’s Mansion was once one of the most famous palaces in the city. The site was restored and renovated (its grounds having housed an air conditioner factory in the 1960s and 1970s) and reopened to the public in 2008. It’s a fascinating place to visit, especially when tourists are being kept out of Beijing (it can get crowded at peak times).

Taking a right at the T-Junction, in the opposite direction from Prince Gong’s Mansion, head east and then north following the road that becomes Qianhai Beiyan. Eventually, you'll pass one of the entrances for 荷花市场 Héhuā shìchǎng. Literally Lotus Market, it was rebranded as “Lotus Lane” (somebody in the Beijing government was a DC Comics stan) when this strip of sad restaurants and cafes opened a decade ago.

Keep walking along Qianhai Beiyan until you see the waters (or ice, depending on the season) of 前海 Qiánhǎi or “Front Lake.” During the winter months, there is usually a lively skating rink here. Continue along the shoreline of Qianhai until the lake narrows and you come upon Silver Ingot Bridge.

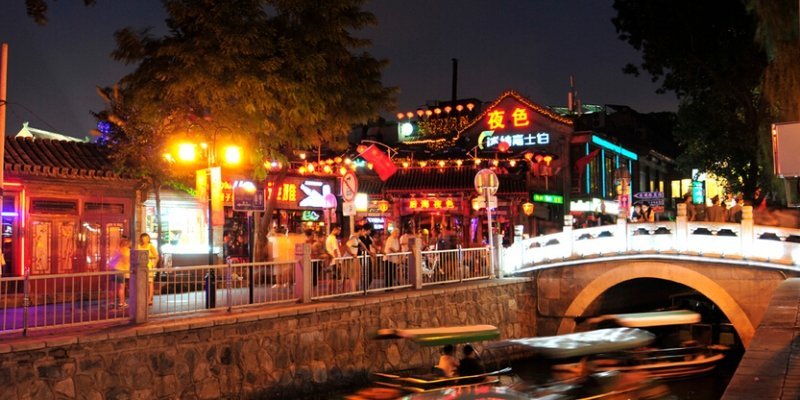

An earlier version of this mini marble arch was celebrated by the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735-1796) in written odes to the most beautiful sights of his capital. Today the bridge is the nexus for the Houhai Entertainment District with cookie-cutter snack shops and cafés/bars featuring identical and ambitiously-priced drink lists. At peak times, the area around Silver Ingot Bridge can be a bit of a madhouse, but after crossing the bridge, head north along Houhai Beiyan, and soon the chaos and commercialism fall away.

The second lake in the chain is Hòuhǎi (“Rear Lake”). It’s the largest of the three Shichahai Lakes and is popular with swimmers in all seasons, as well as paddle boat enthusiasts in the summer months. While not on the lakeshore, a detour down Ya’er Hutong, one street north of the lake, will take you to Guanghua Temple (广化寺 Guǎnghuā Sì). Access to the interior temple, especially with Covid protocols, is intermittent, but you can always try your luck with a cheerful wave and a “Ni Hao!” plus your Green Health Code. The original complex dates to the 13th century but most of the current buildings are the product of later renovations and rebuilds.

The temple is perhaps most famous as a rest home for some of the longest-lived former palace eunuchs, some of whom lived into the 1990s. The most famous is Sun Yaoting (1902-1996), who collaborated on a memoir of his life as a eunuch. (Spoiler alert: He got the chop just a few months before the last dynasty ended, and then he lived a long time. It’s a hell of a story and highly recommended. See the notes below for more information).

Heading back to the shore of Houhai, walk north until you see the large gate of the State Religious Affairs Bureau. This massive complex was once the palace of another branch of the imperial family, father and then son, both known as Prince Chun. This mansion is also the birthplace of Puyi (1906-1967), the son of the second Prince Chun and the last emperor of China.

The Prince Chun Mansion is closed to the public but stretches a considerable distance along Houhai’s northern bank, giving some idea of the grandeur that was once within its high walls. At the far north end of the palace is the former residence of Soong Ch’ing-ling (Pinyin: Song Qingling, 1893-1981), the widow of Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925), who helped organize the revolution that overthrew Prince Chun’s son and toppled the Qing Dynasty in 1912.

Soong was the middle of a trio of famous sisters, the youngest of whom, Soong May-ling (1898-2003), married Sun’s protégé Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975). This section of the mansion is open to the public, and Madame Soong’s house and the surrounding grounds are among the less-visited gems in Beijing.

From Soong Ch’ing-ling’s former residence, continue past the northern edge of Houhai and across Deshengmen Nei Dajie to the last of the three lakes, 西海 Xīhǎi, “West Lake,” which was recently restored. Several areas incorporate sections of plants and reeds, providing habitats for ducks and other birds.

Walking around the lake to the northern shore, there is a statue of mathematician and engineer Guo Shoujing (1231-1316). When Kublai Khan built his city of Khanbaliq on what is today Beijing, the khan wished to upgrade the system of waterways needed to transport tribute from the rest of China to his new capital. Guo Shoujing collaborated with scientists from across the Mongolian empire to design the system of artificial waterways, many of which, including these three lakes, are still part of the city landscape.

Today, Xihai has a peaceful shoreline, but in the 14th century, goods and treasures were offloaded from grain barges floated through Shichahai to a busy industrial wharf, the terminus for a canal system that connected the city with the Grand Canal and the prosperous southern regions of China. On top of the hill behind the statue is the rebuilt Huitong Shrine (Huitongci) which today houses a small museum about Guo Shoujing and the history of Beijing’s waterways.

Just north of the Citong Shrine is the Jishuitan Metro stop and the end of this weekend’s walk.

Know before you go

Many of the sites in this article are open to the public, but be aware that access will involve scanning QR codes and registering before being allowed inside. The security guards and ticket windows are generally pretty helpful when it comes to entrance policy, but experiences may vary depending on conditions in the city and the blood sugar levels of the staff.

Selected English-language sources and further reading

Aldrich, M. A. (2008). The search for a vanishing Beijing: A guide to China’s capital through the ages. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Arlington, L. C., & Lewisohn, W. (2015). In search of old Peking. Vancouver, British Columbia: Soul Care Publishing, 2015. (Originally published: Peking, H. Vetch, 1935)

Cohn, D., & Zhang, J. (2013). Beijing Walks. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Li, L. M., Dray-Novey, A. J., & Kong, H. (2008). Beijing: From imperial capital to Olympic city. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jia, Y. (2008). The Last Eunuch of China: The Life of Sun Yaoting. China Intercontinental Press.

Naquin, S. (2008). Peking: Temples and city life, 1400-1900. Berkeley: University of California Press.

About the Author

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He has lived in Beijing for nearly two decades and is the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, organizing history education programs and walking tours of the city including deeper dives into the route and sites described here.

READ: Weekend Walk: Exploring the Two Towers of Xicheng

Images: chinadragontours.com, Jeremiah Jenne, Yayouxicheng, wikimapia.org, wikipedia.org, justgola.com, english.visitbeijing.com.cn