Walking with the Lamas: A Quick Guide to Visiting Yonghegong

Traveling along the North Second Road past Andingmen, the smell of car exhaust and the nearby canal baking in the August sun is replaced by something more mystical and exotic: the scent of incense hanging heavy in the air, a sign that Yonghegong has finally reopened to the public.

The current Yonghegong complex dates to the late 17th century and was originally the home of Yinzhen, the Kangxi Emperor’s fourth son. Yinzhen succeeded his father in 1722 and moved to the Forbidden City but kept the family mansion and the newly enthroned Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1722-1735) rebuilt large sections of his former home into a part-time imperial crash pad and shrine.

When the Yongzheng Emperor died, his son, the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1799), had to figure out what to do with the place. Not only was it dad’s old palace, but it was also the Qianlong Emperor’s birthplace, and the new monarch's mother was attached to the site.

Convention dictated such an august property couldn’t just be turned over to another relative or recycled for mundane purposes. In 1744, The Qianlong Emperor, in consultation with his spiritual advisors and his mother, who was a devout Buddhist, ordered the main sections of the palace converted into a monastery for Tibetan Buddhism.

Visiting Yonghegong is straightforward. At the moment, you just enter through the gate on Yonghegong Dajie, follow the signs around the edge of the parking lot, rock up to the ticket window waving your passport (which may or not be necessary depending on the day), and somebody will sort you out.

You may see some long lines in the parking lot, and also inside the temple itself. These are to buy religious souvenirs at the gift shops, which are having a "wanghong" moment right now. Unless you are in the market for prayer beads, or are in thrall to Xiaohongshu, you can skip the long lines to get into the gift shops and continue about your visit.

The parking lot is surrounded by four archways. Before it was a parking lot, the space in front of the ticket windows continued east as a hutong toward the nearby Bailin Temple. That route is now blocked for traffic.

Beyond the ticket and security entrance is a path flanked by ginkgo trees which turn a brilliant yellow every autumn.

At the end of the approach is the Zhaotai Gate. Note the multi-lingual signage. From right to left, the languages are Manchu, Chinese, Mongolian, and Tibetan. Many of the steles, inscriptions, and signs inside are also written in these four languages, a reflection of the multi-cultural nature of Qing imperial rule.

Yonghegong still has some of its palace ornamentations. You’ll see yellow rooftops, bronze guardian statues, and quite a few elements that recall sections of the Forbidden City. At the same time, the first courtyard also has a drum and bell tower and a large bronze vat once used to distribute porridge to worshippers during the Laba Festival at the end of the traditional Chinese year.

The hall at the north end of the first courtyard beyond the Zhaotai Gate was the palace entrance in Yinzhen’s time. Today it contains an image of the Maitreya Buddha and the four guardian spirits referred to as “The Heavenly Kings.”

Passing through this hall leads to the second courtyard, which contains some of the more important relics. There are two 18th-century bronze incense burners. The southern incense burner is the subject of an old – and vaguely destructive – legend that tossing a coin onto the uppermost roof of the burner’s iconography is good luck. Today, the monks prefer visitors not throw metal objects at an 18th-century relic. The pavilion in the middle of the courtyard contains a stone stele with an inscription written in four languages by the Qianlong Emperor describing his reasons for patronizing Tibetan Buddhism and his connections to the religion.

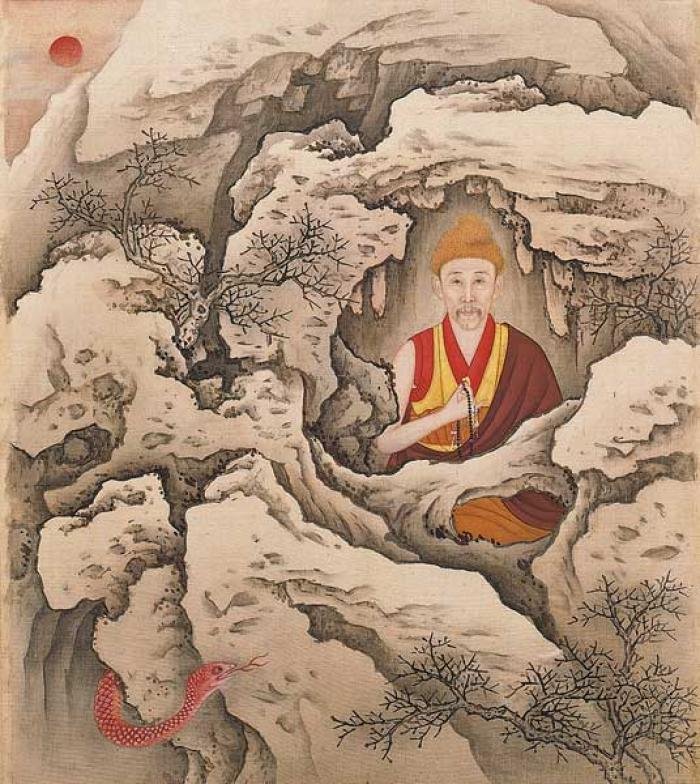

The main hall, also called Yonghegong, contains three icons of the Buddha flanked by statues of the 18 arhats, figures in Buddhism who followed the teachings of the Buddha and finally achieved a state of perfection and enlightenment. The three larger images in this hall are usually identified with the Buddhas of the past, present/historical Buddha, and future. With the notable exception of the Maitreya in the entrance hall, the icons at Yonghegong reflect influences of Buddhist traditions from Southwestern China and Nepal, with many craftspeople from the area participating in the creation and design of the images.

The third building, Yongyou Hall, contains – you guessed it – three more Buddhist icons, including those associated with medicine and longevity. Don’t miss the embroidered image of a Green Tara on the western wall. Monastery legend claims that this is the personal handiwork of the Qianlong Emperor’s mother.

As you walk around Yonghegong, look back through the gates and notice how each courtyard is a level higher than the one before. You’ll also see how the architecture gradually becomes less reminiscent of a Beijing palace and more like a monastery found in the Southwest.

A good example of this transition is the fourth building, the Falun Hall (Hall of the Wheel and the Law). This hall is still used as a worship and study space by the monks in residence. That’s why there are lamps and seats installed. The large statue in the middle is Tsongkapa (c. 1357-c. 1419), considered the founder of this particular denomination of Tibetan Buddhism.

At the rear of the hall are a wooden offering bowl (once a bathtub used by the infant Qianlong Emperor) and a glass-enclosed diorama representing the sacred Mountain of 500 Arhats.

The highlight of Yonghegong – and one of the most extraordinary sites in Beijing – is the recently renovated Hall of 10,000 Happinesses. The hall itself is interesting, with flying buttresses – rare in Chinese religious architecture – connecting the main structure to two side towers, one of which contains a (formerly) working animatronic lotus.

But inside the hall is the main attraction: An 18-meter tall statue of the Maitreya, carved by Nepalese craftspeople from a single sandalwood tree (Guinness certified it, so it must be true). Note that about one-third of the Giant Maitreya is below ground, set firmly to prevent the enormous statue from toppling over in case of an earthquake.

The side pavilions at Yonghegong are also worth exploring. These were used as classrooms and chapels by the monks (who now occupy nearby modern structures). There’s also a museum with artifacts from earlier periods in the monastery’s history, including wild costumes and masks used in whirling dances and ceremonies once performed annually to keep away evil spirits.

Yonghegong is open every day from 9am-5pm (last tickets sold at 4.30 pm) in the summer and from 9am-4pm (last tickets sold at 4 pm) from Nov 1 to Mar 31. You can get there, conveniently enough, by taking Line 2 or Line 5 to Yonghegong Subway Station. Free incense is provided at kiosks throughout the complex for those who wish to leave offerings or prayers.

About the Author

Jeremiah Jenne earned his Ph.D. in Chinese history from the University of California, Davis, and taught Late Imperial and Modern China for over 15 years. He called Beijing home for nearly two decades and was the proprietor of Beijing by Foot, which organized history education programs and walking tours of the city.

READ: Weekend Walk: The Confucian Temple and the Imperial Academy

Images: Uni You, Wikicommons, Author's collection