Photographers of Racially Charged Wuhan Exhibit Apologize After Meeting With Beijing-Based Activist

Samantha Sibanda returned from Wuhan this past weekend with a triumph for her fellow African expats. The Beijing-based Zimbabwean activist and educator had flown there this past Saturday for what turned out to be a drawn-out, two-day, highly contentious meeting with photographers of an exhibit at the Hubei Provincial Museum in Wuhan (首都博物馆) that compared African people to animals, leading to a social media firestorm earlier this month. Sibanda accepted a written apology from those involved before returning to Beijing late Sunday, but that resolution didn't come easily.

In a WeChat post to her followers late Sunday evening, Sibanda said the "intense" meetings "took almost all the strength I had in me" because "I felt like I was trying to convert a non-believer to believe."

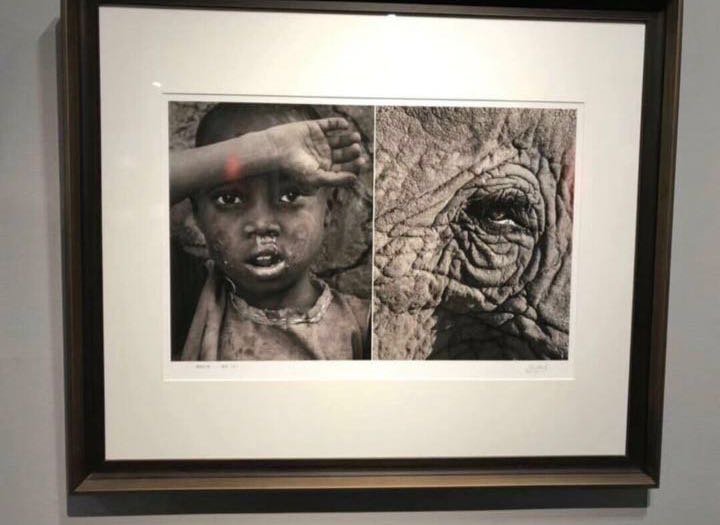

Sibanda – a tireless advocate who has founded Beijing’s Africa Night Speech Contest, Discover Africa Academy, the city’s Pride of Africa Asia Awards, and other initiatives (which you can read more about in this Global Times profile) – first began contesting the controversial Wuhan photo exhibit in early October, after a museum attendee posted an Instagram video showing the installation's photos, and then voicing his disgust. Those photos were hung in pairs – a baby next to an ape, a boy next to a giraffe, and so on. What's more: the collection of photos were titled "相由心生 xiāng yóu xīn shēng" which roughly translates to "outward appearance follows inner reality."

The Instagram video quickly went viral, and when Sibanda learned about it, she coordinated with African activists in Wuhan and across China. Their campaign against the installation was a success, though the museum and the photographers did not apologize after the photos were taken down.

From there, Sibanda took to social media announcing a petition for an apology. Eventually, the photographers agreed to meet with Sibanda and she flew to Wuhan for a grueling meeting that stretched over two days. In a phone interview with the Beijinger, Sibanda said their sit-down began with a few surprises. First, there was not only one photographer, named Yu Huiping, behind the exhibit as she had initially been told; instead, it was Yu and a group of photographer friends who all combined their photos for an exhibit that they deemed to be an art project. Also, the museum's representatives say they were not involved, but instead merely rented that space in their building for the photographers to showcase their work. From there, she learned that the photographers had only visited one small village in Kenya, where they took photos of the Maasai minority in a designated tourist zone.

The photographers began by trying to explain to Sibanda that the exhibit wasn't meant to be offensive, but instead an artistic work inspired by the animals of the Chinese zodiac. One of the photographers told her, for instance, if a Chinese person had their picture placed alongside a panda for comparative purposes it would be an honor, because of how highly regarded those bears are in their culture. Furthermore, the photographers showed Sibanda pictures of impoverished youngsters in a Chinese village and talked about their plans to put on similar exhibits with those images with the hope of raising money for the children.

Sibanda spent six hours at the table with the photographers on Saturday, trying to explain why the installation was so offensive. She said tempers flared and arguments were had, and that night when she went to her hotel the temptation to quit was very strong. Sibanda recalls: "I thought to myself: 'My God! These people will never get it.'" But then she told herself: "Sam, you’re an educator, and you have to educate these people. Because if you don't try, and just dismiss them as racist, Africans in China will always lament it, and will always say 'Oh! If only they knew better.' So I'll tell you where I come from, and by the end of the conversation you will know."

Sibanda persisted in a meeting the next morning, describing the discrimination Africans face in China, especially in the job market. She also showed them news articles about how some African children had been exploited in China, their services for singing and other entertainment being sold on Taobao. What truly persuaded the photographers to apologize, and to stop steadfastly defending their work as art, was a simple question Sibanda posed to the photographers: How would they feel if she took the photos they had taken of impoverished Chinese children, and displayed them at a museum in Africa under the banner "This is Asia?"

"That's when they began to realize that they were looking at Africa as a country, and that their outlook was wrong," Sibanda says. One of the photographers is a higher-up in the education system, and Sibanda told him: "You are so influential in your community. Children read what you write into their curriculum. If you give them positive photos of Africa, they will believe you. You can turn this around."

As the meeting drew to a close Sibanda says she could see that some of the photographers were fighting back tears, before openly weeping. "I could see their sincerity," she recalls. An excerpt from the apology reads:

"We extend our sincere apology for the controversy over this exhibition. We sincerely hope to gain understanding from all friends, African friends in particular and we will continue to make contributions to the mutual understanding and traditional friendship between the people of China and Africa as always."

Better still, the photographers pledged to depict Africa in a more positive, truthful, and nuanced light with a forthcoming photo exhibit. Aside from returning to Africa for more photos, they also invited Sibanda to put on her annual Africa Night Speech Contest in Wuhan, so that attendees who saw their exhibit, and left with the wrong impression, could have their mindset changed in the same way that Sibanda had done for the photographers.

News of the photographers’ apology was heartening to Gregory Olawoyin, the Wuhan-based Nigerian expat that worked with Sibanda and other activists to have the exhibit taken down a few weeks back (he spoke to the Beijinger under the condition of anonymity at the time, but has since agreed to have his name on record). He also praised Sibanda’s tireless work ethic, saying, “It was an opportunity to educate, and she took that with aplomb.”

Sibanda says she's overjoyed that this teachable moment became a success in the end, adding "This all just reinforces a message that I want to impart on each and every African out there: we have a job to educate such people, before labeling them racist. It’s our job to educate because they don’t know, and everyone should take it upon themselves to educate others about where you come from, and to impart the truth about your home."

More stories by this author here.

Email: kylemullin@truerun.com

Twitter: @MulKyle

Photos: Shanghaiist, Samantha Sibanda

Related stories :

Comments

New comments are displayed first.Comments

![]() TRMalex

Submitted by Guest on Thu, 11/02/2017 - 07:32 Permalink

TRMalex

Submitted by Guest on Thu, 11/02/2017 - 07:32 Permalink

Re: Photographers of Racially Charged Wuhan Exhibit Apologize...

Very good news!

[snarky comment] Now let's see her trying to convert a believer to non-belief - that's an entirely different feat... [/snarky comment]

Validate your mobile phone number to post comments.