History on a String: How Chinese Kite Flying, and Kite Watching, Are So Much More Than a Hobby

Beijing may have a reputation for filthy, dreary grey skies, but by spring things are different. At least’s that’s the case on clear blue, mild, windy post-coal burning April days at Olympic park, where Liu Bin flies brilliantly colorful kites as not only a hobby, but also part of an age old Chinese tradition.

As owner of the Nanluoguxiang adjacent Three Stone Kites shop – a family business that was founded decades ago by his grandfather – Liu knows how to not only fly but also craft the string tethered silk and and paper dragons, butterflies, and other creatures that act as gorgeously soaring pieces of Chinese iconography.

“Outside of the downtown core is the best,” he says of his favorite places to fly kites, adding that Olympic park is his favorite because it has “No trees, no traffic, and few people. Years ago, I’d fly kites in Tiananmen Square, but now I do it in Olympic Park more, because there’s so much more free space.”

Aside from pure enjoyment of getting the kites off the ground, Liu says he also loves how the hobby can offer foreigners insight into Chinese culture. Flying his colorful bat kites, for instance, has lead to conversations with passersby about how “bats are associated with vampires and scary stories in western culture. And foreigners have told me they were surprised to learn that bats are auspicious and lucky in Chinese.”

Liu also likes telling people have the different colors on kites have different meanings, and even the different way they fly on a given day can signify things like luck or beautiful wishes.

While kite flying may seem like a fun, albeit quaint, pastime enjoyed by elders in parks, it was actually once an integral practice in day-to-day Chinese life. The Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding credits a Shandong philosopher named Mo Di with inventing the kite after observing how leaves blow in the wind. It goes on to say that early Chinese kites were built by armies to be massive enough to hoist soldiers heavenward for reconnaissance or to “scatter propaganda leaflets over hostile forces.”

Kaleidoscope Cultural China, meanwhile, describes how messages were sent and land measurements were made with kites in the Han Dynasty, while the Five Dynasties era saw a kite tied to a bamboo whistle making “a sound like the zheng—a 21- or 25-stringed plucked instrument in some ways similar to the zither— under the force of wind” leading it to be called “‘fengzheng’”, meaning “zheng in the wind.”

But compelling as that historical context may be, Zhang Guobin forgets all about it once his kites are in the air. Zhang is a Beijing retiree who, at both Olympics park and at Guangqumen bridge near (near Guangqumen Wai station on Line 7), flies not only traditional kites but also newer renditions covered in UFO-esque LED lights, and he says simply: “I enjoy kite flying because it’s relaxing and fun.”

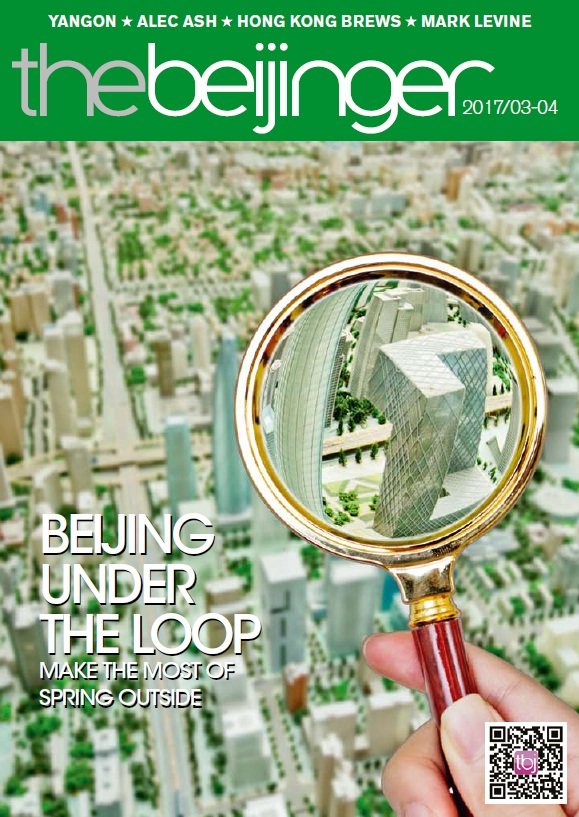

This article first appeared in the March/April issue of the Beijinger.

More stories by this author here.

Email: kylemullin@truerun.com

Twitter: @MulKyle

WeChat: 13263495040

Photos: Uni, Kyle